"The Living": Courage and compassion in the face of cataclysm

A close look at the Dartmouth Department of Theater's fall 2019 Mainstage production.

HANOVER, NH—If a plague or mass disaster struck your community, how would you respond? This is the question at the heart of The Living, a play by Anthony Clarvoe, November 8 through 17 by the Dartmouth Department of Theater.

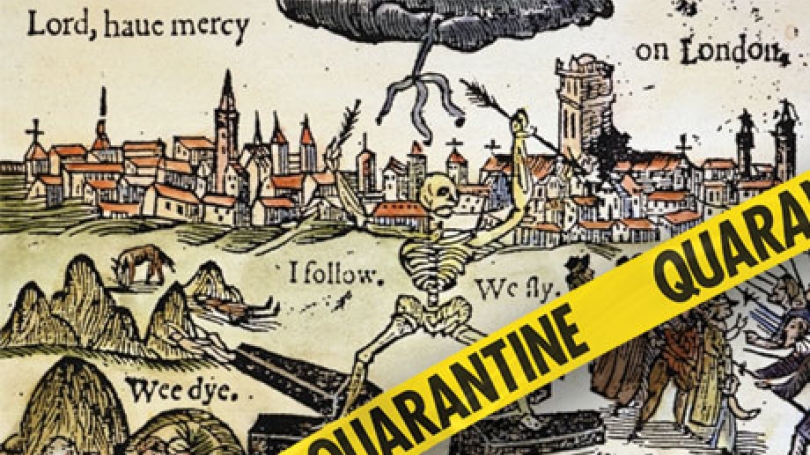

Set in London, 1665, when the city was in midst of an outbreak of bubonic plague that would ultimately kill over 20 percent of the city's population, The Living examines the whole range of human behavior in response to a sweeping threat--from heroic attempts to help others or address systemic issues, to reflexive and even heartless self-protection.

The world The Living paints is scary. Attempting to avoid contagion, people don't touch or breathe on each other; papers pass from one person to the next with giant tongs. Those doctors who haven't fled protect themselves with bizarre masks that transform them into terrifying messengers of death. Heartbreaking, bitterly funny, and deeply moving, The Living celebrates the power of courage and compassion to combat fear and darkness.

Written in 1993 as a response to the AIDS crisis, The Living has up-to-the-minute relevance today, when the developed world is essentially one jet ride away from virulent diseases like ebola, said Dartmouth Department of Theater professor Jamie Horton, the play's director. "In today's world, disease anywhere is disease everywhere. Think about the spread of AIDS and multiply it tenfold. Deadly epidemics are not things that happen to 'other' people." The play is also relevant to the looming threats of food, water and shelter challenges due to climate change, he noted.

The play's real subject, however, is our souls. Wrote the Denver Post in 1993, "The Living is not about death. Rather this remarkable, riveting drama is a compelling confirmation of life. And although it's set more than three centuries ago, Anthony Clarvoe's two-act parable … maintains ... stunning immediacy ... Often bitterly funny, often ineffably sad, this is the story of a few brave sometimes reluctantly so people who stood fast, doing what needs to be done."

Horton, then a member of the Denver Center Theatre Company, played the role of John Graunt in the 1993 premiere production. One of several historical characters in the play, Graunt was a London haberdasher who became intrigued by the birth and death records that had been kept in English parishes since 1532. Noting trends in birth and mortality rates along gender, geographic and other lines of distinction, he's considered the parent of demography. His analyses reports were a critique of government attempts to minimize the 1665 plague's horrifying impact, and his analyses allowed him to predict that outbreak three years before it occurred. (His warnings went unheeded.)

The Dartmouth production refers to the historical layers in its design, with a set that mimics the Drury Lane Theatre of 17th-century London, and with costumes from that period but incorporating such modern elements as hazmat suits. One pure 17th-century element is an outlandish "plague mask" that will be worn at times, resembling a huge beak and meant to shield the wearer from contagion.

The play's modern-day relevance and more will be explored in a free public pre-performance talk, "The Politics of Plague in 2019," on Saturday, November 16, 7 pm, Top of the Hop. Elizabeth Talbot, MD, and Horton will discuss how The Living resonates with today's international health crises of tuberculosis, ebola and HIV, and how these connections should empower rather than alarm. An Associate Professor at the Geisel School of Medicine, Talbot has been an outbreak investigator for the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization and the NH Department of Health and Human Services where she serves as the Deputy State Epidemiologist. Moderated by Laura Edmondson, Associate Professor of Theater.

Talbot spoke with the entire cast at an early rehearsal and has advised the production team during the planning process. Each theater department Mainstage production for the past several years has included a scholar from outside of the theater department to help deepen the cast's and directors' understanding of a given play's context, and to engage in "critical conversations" open to the public, like the November 16 event.

The public is also invited to the following events:

- Opening Night Reception, Friday, November 8, post-show, the Top of The Hop, cash bar available.

- Discussion with the Cast and Creative Team , Friday, November 15, post-show, Moore.

1665—and Today

The Living's subject is a major event in the annals of Western European civilization, the great plague that swept through London in 1665-66, killing, at its peak in the summer of 1665, about 1,000 persons each hour. The facts of the cataclysm survived thanks to the extraordinary testimony left by contemporary witnesses, including Samuel Pepys, who countered the government's attempts to downplay the death numbers.

Wrote Daniel Rose, who directed the premier production: "Most scholars agree that there was gross underreporting in the weekly Bills of Mortality, caused by families fearful of retribution, and by parish clerks who conspired to prevent widespread panic. By mid-June [in 1665], over a hundred plague deaths per week were announced in the bills, although the real numbers were much higher. The government's remedy was to hire older women as 'searchers of the dead'—if plague was found, the city quarantined the infected household, nailing shut the doors and posting watchmen to guard against flight. By early July, almost everyone who could afford to leave the capital did so. The King and his court, the Privy Council, families of means, and almost all clergy and physicians fled, leaving the general population to fend for themselves. Those who tried to leave the city after July found the people of the surrounding towns fiercely guarding the roads, turning back anyone from London. The dire lack of doctors and hospitals, coupled with the flight of the clergy, caused great hardship for those who were left behind. A few brave physicians stayed to tend the sick as best they could, wearing protective clothing and beaklike leather headpieces stuffed with herbs. Nonconformist clergymen—whose presence had been outlawed in the Restoration—returned to minister from vacated pulpits. Funerals were forbidden, thus burials took place at night in massive pits dug outside the city walls, attended by the few maverick preachers willing to provide services for mourners."

As the play roams about London, picking up the threads of several stories, we learn many of the medical treatments (or what passed for treatments) in caring for victims of the plague; and, through several scenes set in the chambers of the Lord Mayor of London, we see key political and social leaders of England reacting to the crisis. A dandified member of King Charles II's court reacts with horror, for example, when he finds out that the government may have to pay some of the medical expenses for the plague victims.

Wrote Rose: "As is so often the case in human affairs, fear provoked desperation, despair, and the common response to flee. However, London's Great Plague also saw many acts of uncommon courage and compassion. The Living chronicles an extraordinary effort to survive, not just as individuals, but as a society. Historical accounts are full of behavior that illuminates both the worst and best that human beings are capable of. England's institutional response to this epidemic allows many interesting comparisons to crisis in our own times. And the response of the individuals in this play allows us to look into our own hearts - to consider how we will respond if those around us fall."

The Living was one of the earlier works of a playwright who's since become a leading playwright and mentor to younger writers. Clarvoe has received the American Theatre Critics, Will Glickman, Bay Area Theatre Critics, LA Drama Critics, Elliot Norton, and Edgerton New American Play awards; fellowships from the Guggenheim, Irvine, Jerome, and McKnight Foundations, NEA, TCG/Pew Charitable Trusts and Kennedy Center; commissions from South Coast Rep, Mark Taper Forum, and Playwrights Horizons; and the Berrilla Kerr Award for his contributions to American theater. He is a regular instructor at the Playwrights Foundation, Stagebridge, and Playground. The Living has received over 40 professional and amateur productions.